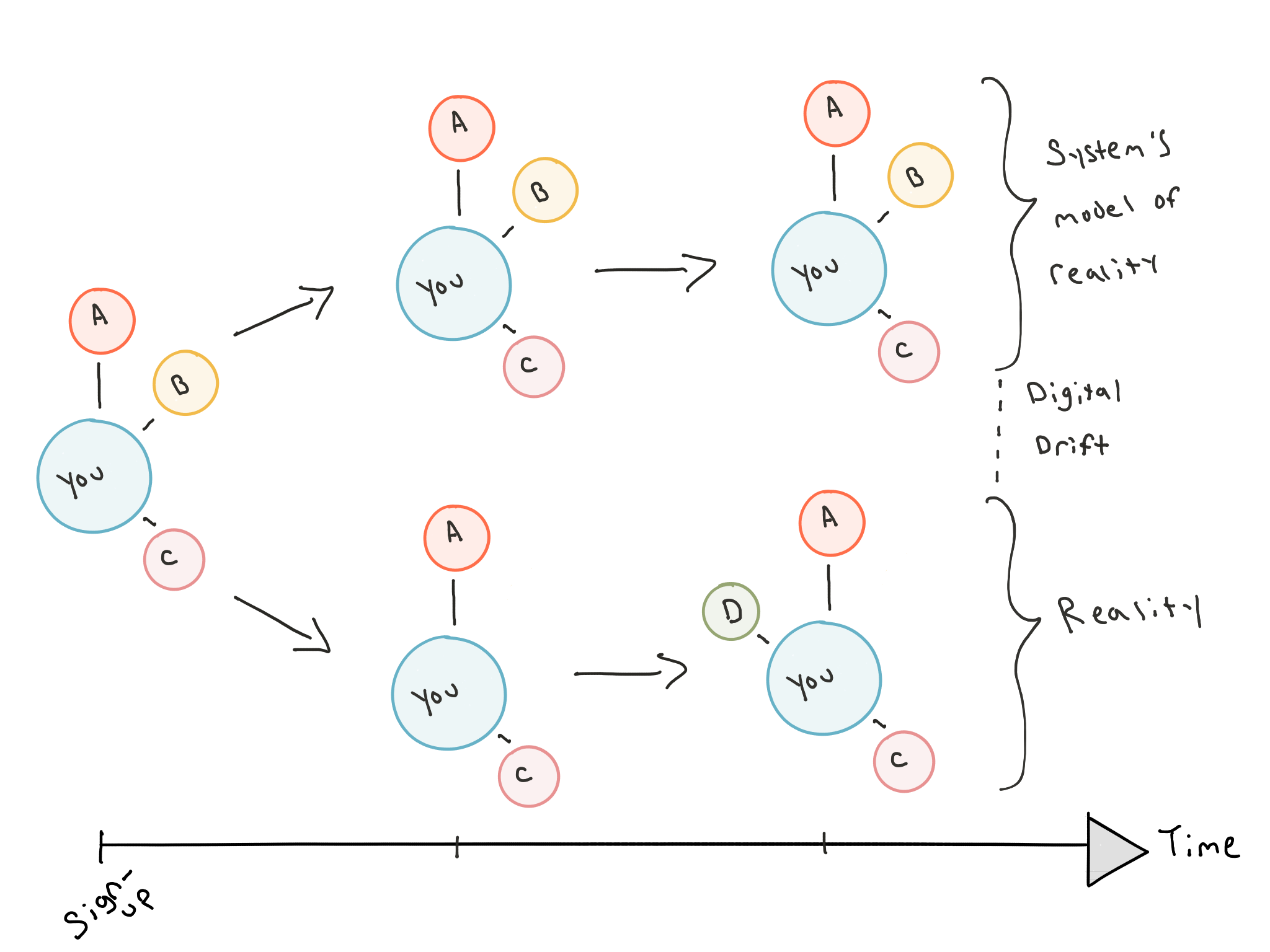

Digital drift

05 Mar 2018Why do some networks—like Facebook’s graph—seem to drift into irrelevance over time? Putting the product’s (ever-crowded) feature set aside, I think there’s a fundamental assumption baked into services today causing this: edges (friendships, follows, subscriptions, etc.) between nodes existing indefinitely. Sure, you can always unfriend, unfollow, or unsubscribe from accounts that are no longer of interest. But these actions aren’t encouraged. This is counterintuitive. By dissuading users from pruning their graphs, services boost short-term “metrics,” at the risk of causing the network and reality to diverge—eventually leading to churn altogether. Concretely, the combination of my FB feed containing posts from folks I’ve been out of touch with and the weight of the verb “unfriending” causes the network’s snapshot of my social reality to become increasingly inaccurate. It’s healthy for my inner circle to change over time; Facebook makes it feel unhealthy through the connotation of “unfriending.” Let’s call the gap between a system’s model of reality and reality itself “digital drift.”

After giving the concept a name, I’ve noticed it crop up elsewhere. To-do apps are another instance. At their core, they attempt to model the state of the tasks we need to accomplish. However, without regular upkeep, they go stale in being able to answer the question “what should I be working on right now?“—causing a loss of trust in the system.

How can services mitigate digital drift? Two approaches come to mind: periodic “reality reconciliations” and malleability.

Reality Reconciliations

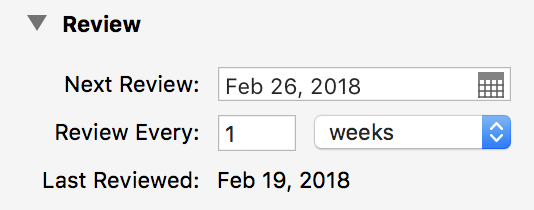

Reality reconciliations are deliberate attempts to update a system’s model of the world. These attempts can be explicitly encouraged or initiated by the user. OmniFocus does a wonderful job at encouraging the former. Each project within the task management system can be assigned a “review” cadence.

Reviews are prompted at the chosen intervals, allowing users to groom tasks within a project. By reconciling items in OmniFocus and reality, it’s easier to trust the system—opening the app is met with a snapshot that better approximates your life instead of irrelevant cruft.

Rosemary Donahue (somewhat hilariously) provided an example of user-initiated reality reconciliation in her post “The Strange Reason I Love Facebook Birthday Notifications.” On birthdays of folks she no longer considers friends, she quietly unfriends them—a Facebook Irish Goodbye. This may seem harsh, but Rosemary elaborates on how it gives her more digital space.

“It may sound heartless, to unfriend people on their birthday, but I like to think that they won’t notice I’ve done it on a day that other people—presumably, people they’re still in touch with—are showering their timeline with love, affection, and, of course, GIFs. While I know that I could simply unfollow rather than unfriend on Facebook…, I don’t understand the need to keep up digital pretenses…I prefer to leave people’s Internet lives the same way I leave parties: quietly, with no goodbyes, and perhaps with a few snacks in my pocket.”

OmniFocus Reviews and Rosemary’s approach counteract digital drift. Still, these forms of reconciliation feel like half-steps and require non trivial effort, which brings us to a way around that: malleability.

Malleability

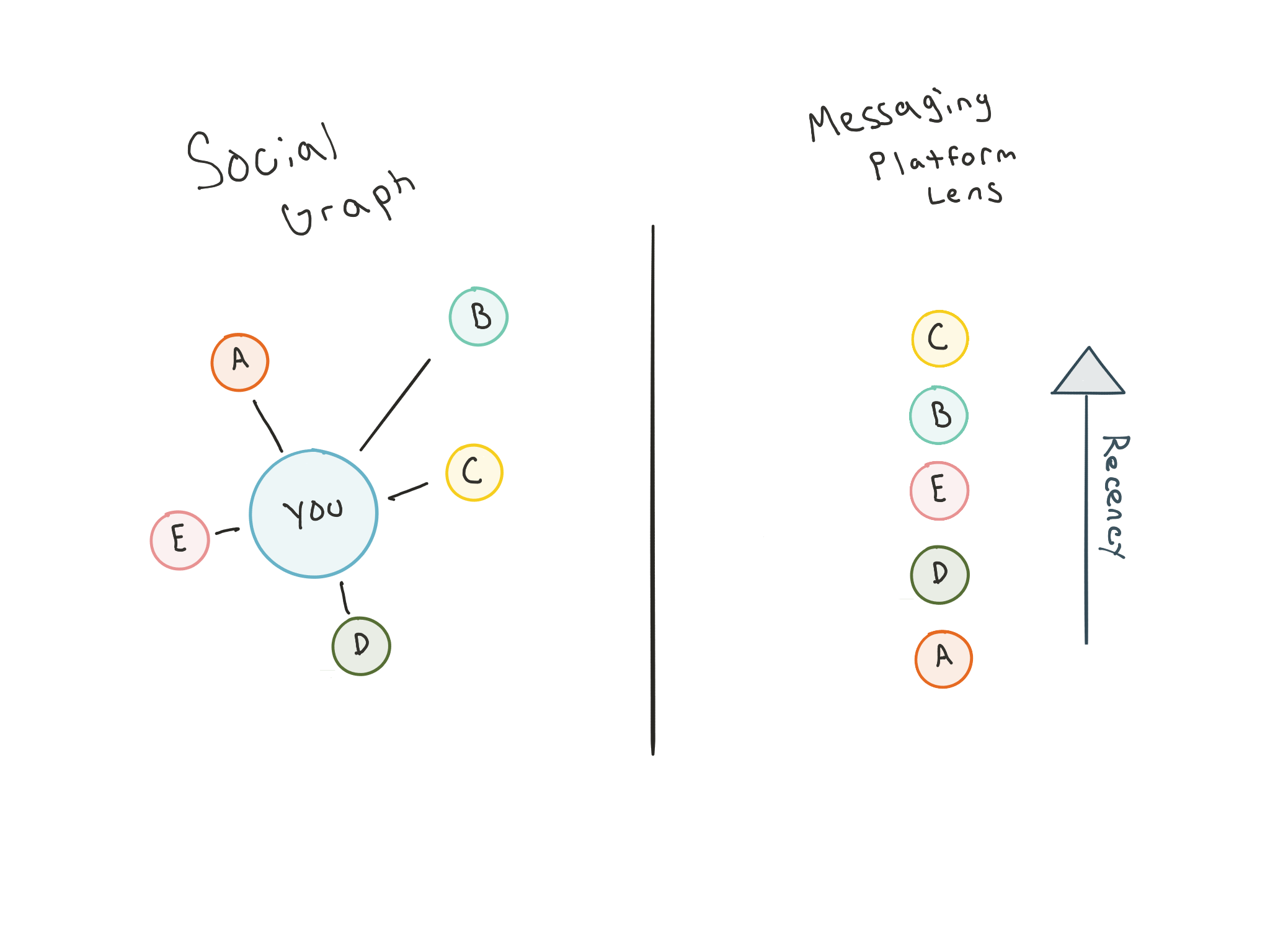

What if the networks (and apps, systems, etc.) we use were malleable? Social graphs would frictionlessly evolve as friends come in and out of our lives. Messaging platforms seem to poke at this by sorting threads by recency. Those we’re in touch with float to the top and everyone else gently lands a few scrolls away—adjusting our lens on the social graph of the platform along a single axis: time. Of course, there’s an inherent bias here, as it prioritizes recency over longer-term friends, loved ones, and relatives we may talk to on infrequent timescales.

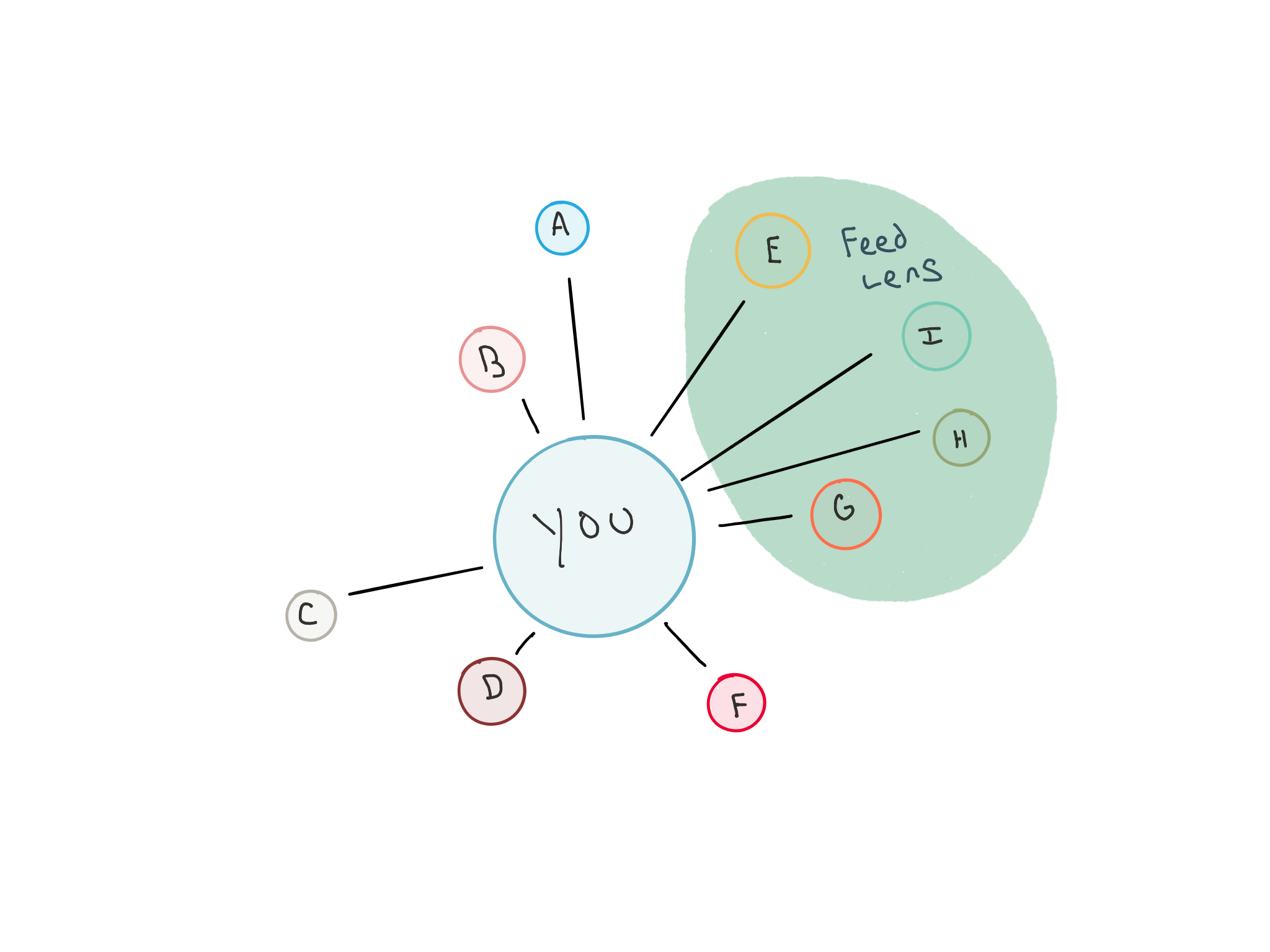

Algorithmic feeds are another attempt at malleability. Unlike sorting, algorithmic feeds use multiple dimensions to shape our view of the graph. For example, engagement™ and pauses in scrolling on another user’s posts might cause them to show up more frequently in the feed. We can view this as the network updating the edges of your social graph in real time.

Sorting and algorithmic feeds have a major shortcoming: they can’t prune our graphs. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not advocating for cutting everyone outside of one’s inner circle from their life—those “older” edges in the graph might actually be ripe with latent serendipity. But, there is a cognitive overhead involved with keeping others in our lives, even digitally. We’ve observed this in the “real world” through Dunbar’s Number, which suggests that the “cognitive limit to the number of people with whom one can maintain stable social relationships” hovers around 150 people. I wonder if there’s a unique analog to Dunbar’s number for each of the services we use (dependent on the atomic units1 of the network, emotional weight attached to edges, etc.).

A lightweight way to rein in digital drift could be edges with expiration dates. As an example, what if we had the ability to follow an account for X months. When X months comes around, the edge silently drops—letting our graph reconcile with reality. Functionality like this could be especially useful on Twitter. I’ll often follow someone when they’re covering an event or aligned with a temporary interest of mine. Despite the social awkwardness of “following someone for a finite amount of time,” it’s more honest to realize that not everyone you follow should continue to be in your graph forever (the default assumption of most services). The permanence of the Internet is simultaneously a strength and an Achilles’ heel. Rethinking the dynamic of edges between nodes is going to require a heavy dose of thoughtfulness. Although, I think the next generation of networks will need it to avoid inevitably drifting.

We’re approaching a stage where people’s main “life”—to an increasing extent—happens in digital realms. As such, the gap between reality and its snapshot embedded in systems affect our usage, trust, and relationship with them. The model of my social reality approximated by Myspace? Archaic. My Facebook graph? Becoming more irrelevant by the day. Perhaps the best services mirror reality and digital drift is a trailing indicator of that mirror being broken.

In meatspace, there are no reconciliations, they happen naturally. Edges fade by default; if you stop calling a friend, they’ll slowly vanish from your life. So, mitigating digital drift might be a lost cause, since digital worlds are inherently durable. What if we took the opposite approach—requiring maintenance to keep edges around and not requiring maintenance for them to drop? That’s how our world works after all.

Special thanks to Can and Nikhil for feedback on early drafts of this entry.

Footnotes and related reading:

-

Twitter : tweets, Facebook : posts, Snapchat : snaps, … (if we’re considering the primary actions taken on each platform). ↩