Deriving reactive from imperative: an introduction to duals

26 Jul 2019While Apple’s Combine framework didn’t take center stage, its implications on our community certainly will for the next decade. We now have a first-party toolkit for functional reactive programming (often abbreviated “FRP”) that packs an intimidating namespace of operators, opaque abstractions, and features even Combine’s open-source counterparts omit like backpressure.

This post aims to unpack those choice adjectives, ‘opaque’ and ‘intimidating,’ that are often lobbed at FRP when folks retreat to its more familiar sibling, imperative programming. We’ll start by contrasting the approaches and covering some history before deriving Combine’s foundational types, Subscriber and Publisher.

Imperative and Reactive (er, Declarative)

FRP is a way of handling data flow in a declarative style of computation. At its core, declarative programming focuses on the what of our programs, whereas imperative is focused on how to achieve some end, down to the exact commands and control flow.

“An analytics event should only fire once on view appearance.” As opposed to “we’ll bookkeep that we’ve only fired the event once by adding a boolean to our view and making sure we only flip it, when appropriate.”

“The screen should remove its loading view only when these three API requests have returned successfully” over “here’s three semaphores that signal on each respective API request. Use them to know when to finally remove loading view.”

To further ground this distinction, here’s an example I often run into while working on Peloton Digital, updating an already-rendered cell in response to a member’s action. For instance, when a member (un)bookmarks a show, we want to update the state of every cell corresponding to it. The first snippet takes a declarative approach and the latter, more imperatively. (Pardon the RxSwift—Combine’s iOS 13.0+ requirement prevents us from using it in that target…we’re luckier in others).

Now, imperatively:

Transformations and relationships are the focus of the former approach. “Listen to these notifications, filter in on the firings we want to consider, map them as booleans, merge the sequences, lift the boolean to the appropriate bookmarked state image, and bind it to our button. Then, dispose of the sequence’s lifecycle when disposeBag deinitializes.”

Imperatively, all of the above is considered to a mechanical level. Details like guard’ing out control flow, managing capture semantics, explicitly calling UIButton.setImage(_:for:), and remembering to remove the observer farther away from these attachment points in source all have to be spelled out.

History

Reactive programming has been around for some time. It draws inspiration from “Alan Kay’s 1969 paper The Reactive Engine, [and] modern use of the term ‘reactive programming’ refers to ideas started in Conal Elliot and Paul Hudak’s 1997 paper Function Reactive Animation.” However, the paradigm caught wind in late 2009 when Reactive Extensions (Rx) for .NET was released, outlining a specification for other languages to conform to and, by extension (pun intended), join the Rx family of libraries.

ReactiveCocoa (“RAC,” for short) provided an Objective-C implementation of reactive programming in May 2012—and was ported to Swift in its 3.x release and is now split into two repositories: one under the same name and the other being ReactiveSwift. RxSwift followed suit with its first tagged release landing in May 2015. Comparing the two is a post in and of itself, yet, the abstraction behind the implementations is what matters. And sharing that abstraction allows different codebases to build on the same foundation.

How have (Reactive|Rx)Swift been around for at least four years and still not become the common tool of choice for building applications? The answer isn’t straightforward—still, we can list a few culprits:

- The frameworks, despite being open-source, are external dependencies and that’s a risk to consider when working in Apple’s ecosystem.

- FRP often makes code easier to reason about in the long run, at the cost of a steep on-boarding curve and having a team of peers who are well-versed and bought into the paradigm.

- Traditional education focuses primarily (if not exclusively) on imperative programming. So, while reactive programming is the other side of the same coin, its incidental complexity is only exacerbated by unfamiliarity.

If I were to guess, the unfamiliarity with and months-long patience required to grok FRP keep folks at bay. Helping others climb reactive programming’s learning curve will involve re-thinking educational material on the topic. Thankfully, reactive programming has roots in mathematics we can rely on and deriving the core types in Combine involves “flipping the arrows” of imperative primitives, IteratorProtocol and Sequence, or as I’ll show, defining their duals.

Duals

“Dual” is one of those five dollar words for a five cent idea. Chances are you’ve used a dual in everyday programming.

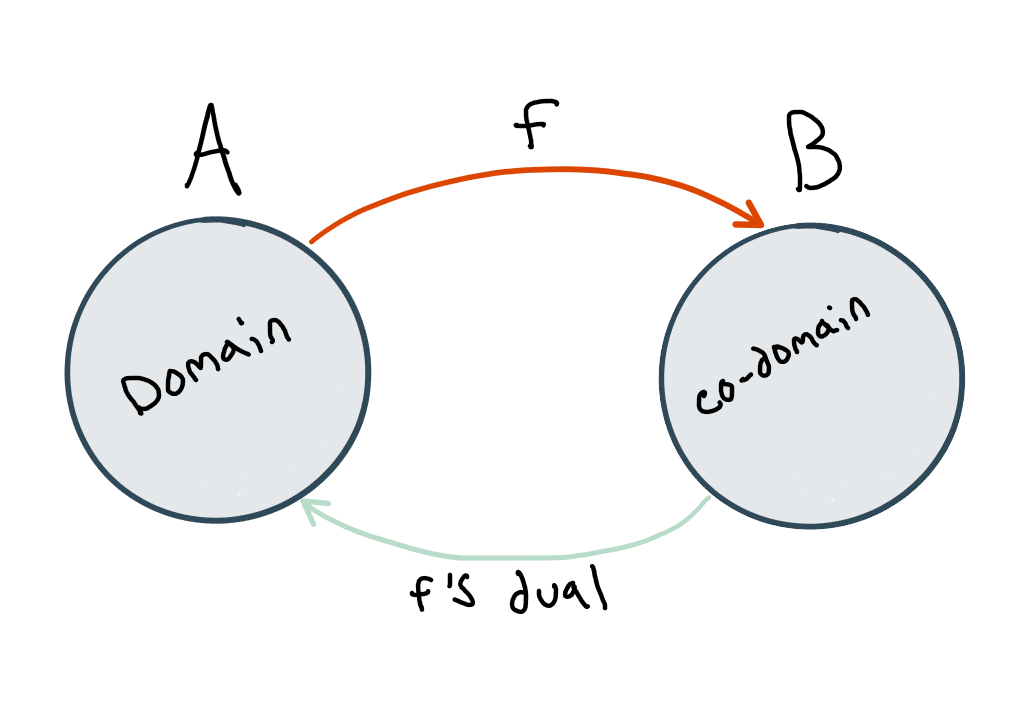

Moreover, I’d wager anyone who has been introduced to a mathematical function, i.e. a mapping from one set, say A, to another, say B, ran into their first dual. If we call such a function f, then A is its domain (the starting set) and B is its range (the target set). Or, you might’ve heard B referred to as the co-domain—and that “co-” prefix connotes a duality. If we “flipped the arrow” of f to instead start from B and point towards A, then B would be our domain.

Let’s formalize “flipping the arrows.”

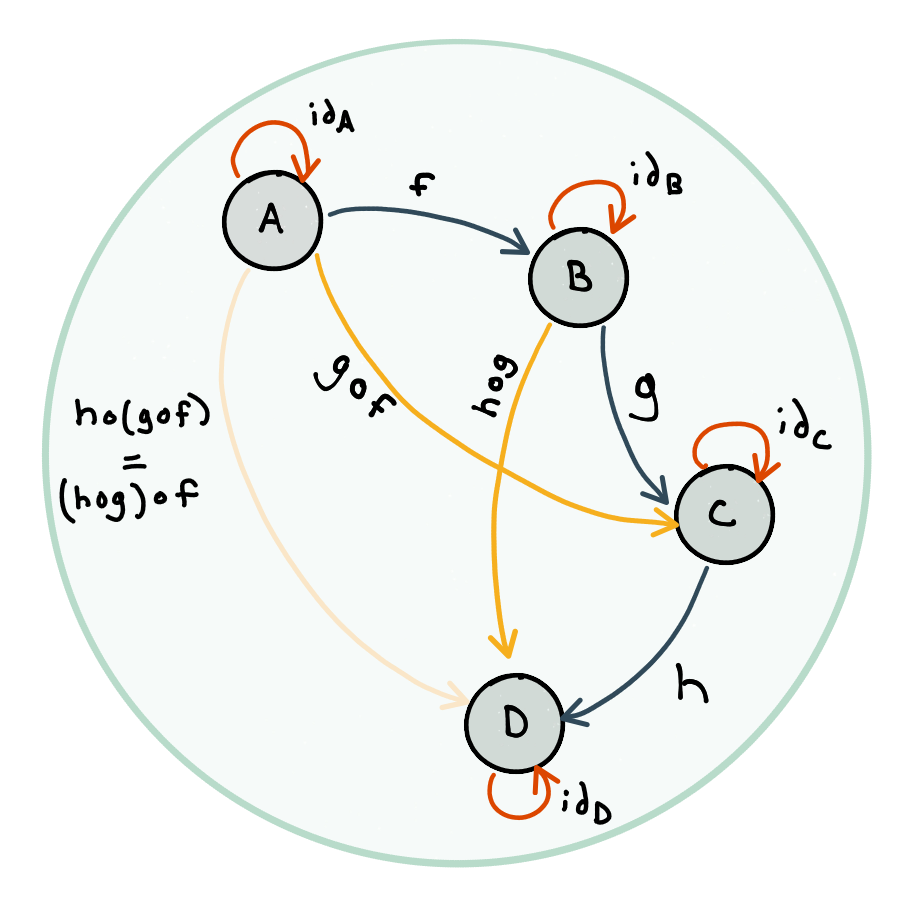

Duals are most readily seen from a category-theoretic perspective. Category theory is the study of structure and composition and its fundamental unit is, you guessed it, the category. Categories have a few properties:

- It consists of objects…really, that’s all the detail we get about them. That’s also the beauty of it. Category theory erases the details that delineate branches of mathematics to show their similarities.

- There are directed “arrows” between objects and those arrows must include one for each object to itself (an identity arrow) and compose associatively (denoted by

g∘f, iffis applied first, followed bygorg(f(x))in a programming context). Put another way, an object,A, must have an arrow to itself, and if it has another pointing towardsBandBhas one towardsC, then there exists an arrow fromAtoCrepresenting the composition of those two arrows.

From this construction, category theory provides a template for a lot of mathematics. If we consider the objects to be the types in our programs and arrows to be functions between them, then we almost1 have a category.

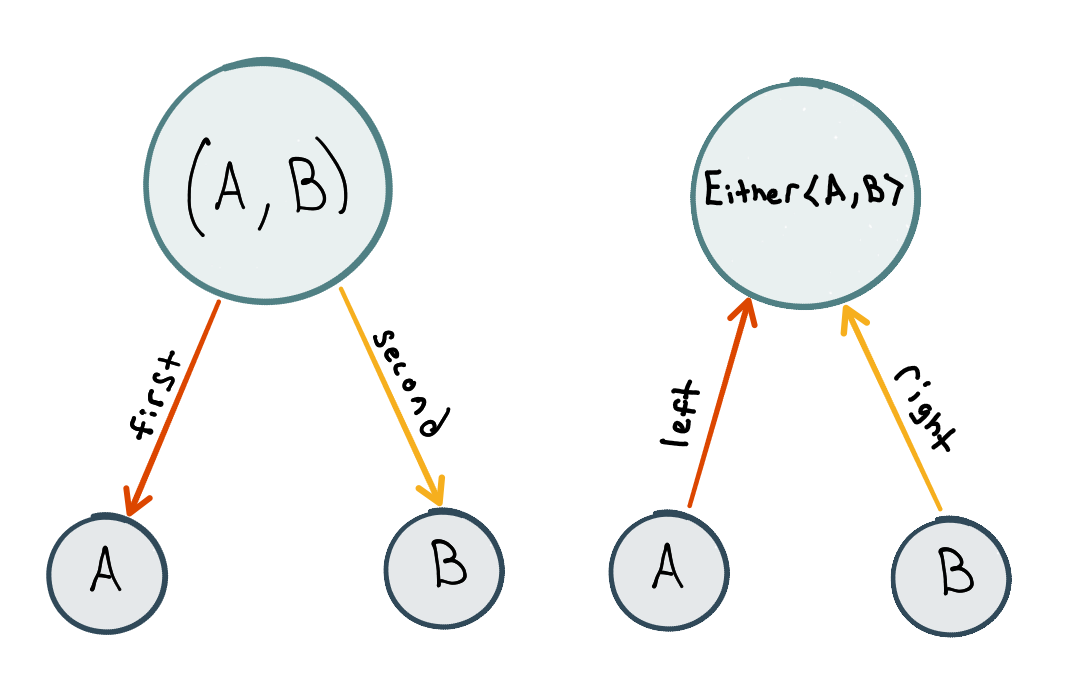

Now we can start flipping arrows. For every construction, we can reverse the arrows to construct a dual. Below is a sketch of defining a tuple in terms of objects and arrows and to its right is the dual, which happens to be our dear friend, Either.

Hiding in Plain Sight

With the definition of duals at hand, you start to notice them…everywhere.

Structs and Enumerations

The above sketch of (A, B) and Either<A, B> (and generalizing to higher arities) shows the duality between structs (named tuples) and enumerations.

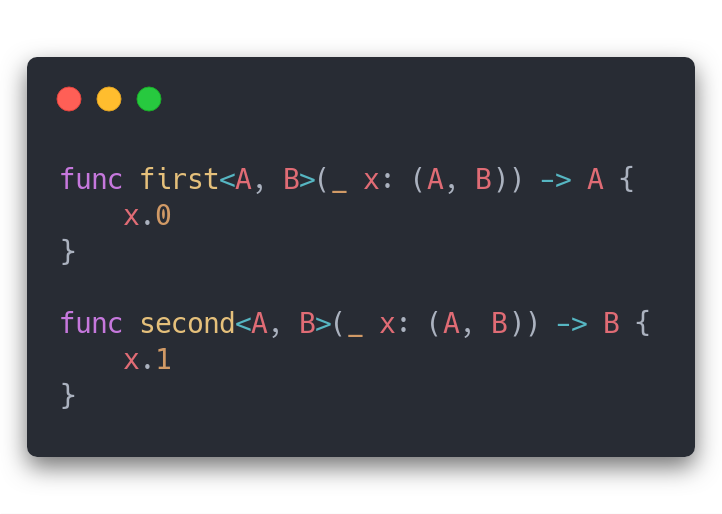

A tuple is the “smallest” composite type of A and B such that there exists projections from (A, B) back towards A and B—the projections are most commonly called first and second.

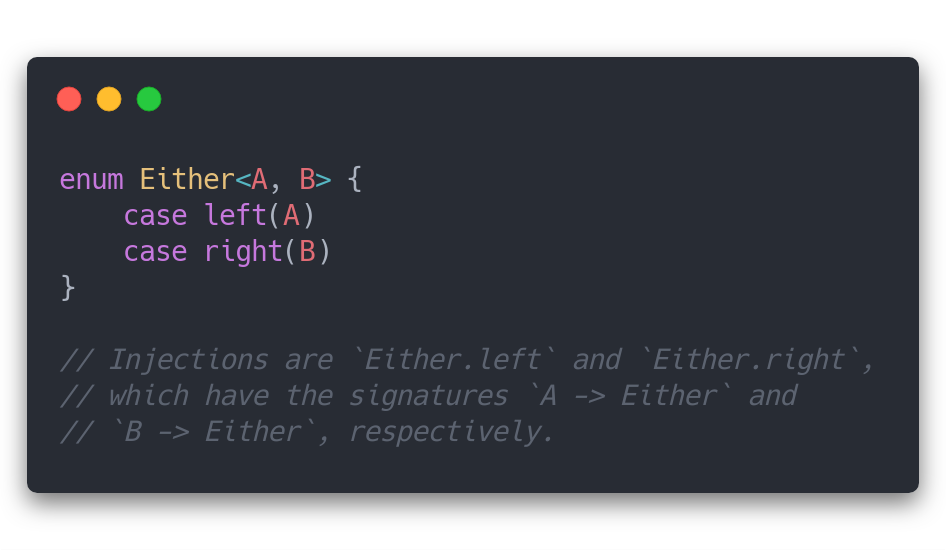

Dualizing, Either<A, B> is the smallest type parameterized on A and B such that there exists injections from A and B into the type. If we define Either as follows, Swift provides those injections for free:

Projections down towards and injections up from a struct or enumeration’s component types are the arrows being flipped. This duality is often conveyed by calling structs product types and enumerations, co-products.

Even wilder is that, despite this duality, language design often has a bias towards one side of the dual. e.g. structs can be defined anonymously with tuples and enumerations…can’t. Properties of structs can be accessed by dot-syntax or key-paths, whereas associated values in enumerations have to be pattern matched out.

Side Effects and Dependency Injection (Co-Effects)

Any function that makes an observable change on the outside world—writing to disk, firing an analytics event, logging—can be viewed as a function with a sort of hidden output. Time to flip the function arrow. What is an input from the outside world a function needs to execute (e.g. a shared singleton or the current system time)? Typically, we call this dependency injection—or, with our “co-“ prefix, they’re co-effects!

From IteratorProtocol and Sequence to Subscriber and Publisher

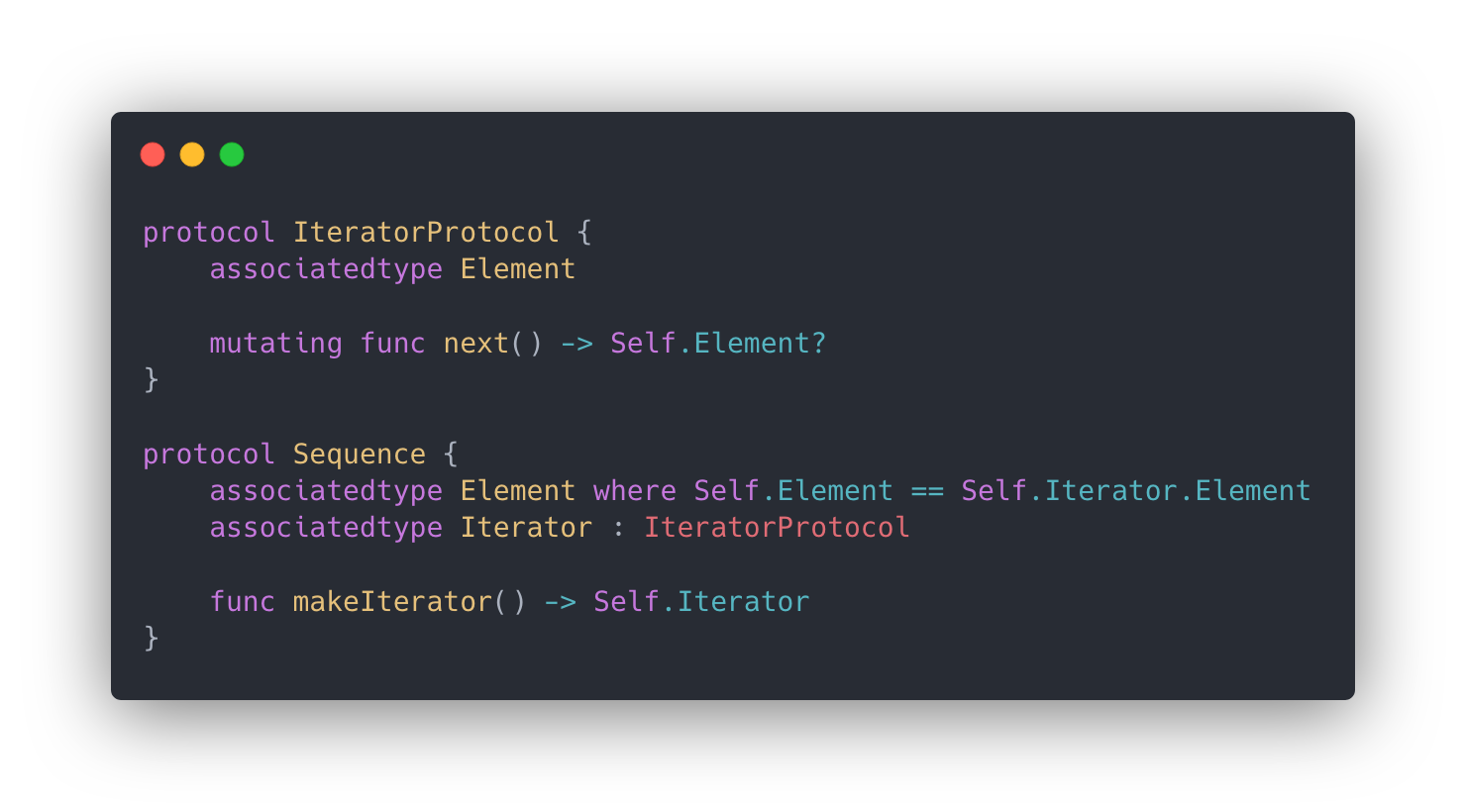

The duals we’ve covered—products and co-products and effects and co-effects—are primers in seeing the duality between imperative and reactive programming. To start, here are abbreviated definitions of the fundamental imperative types, IteratorProtocol and Sequence:

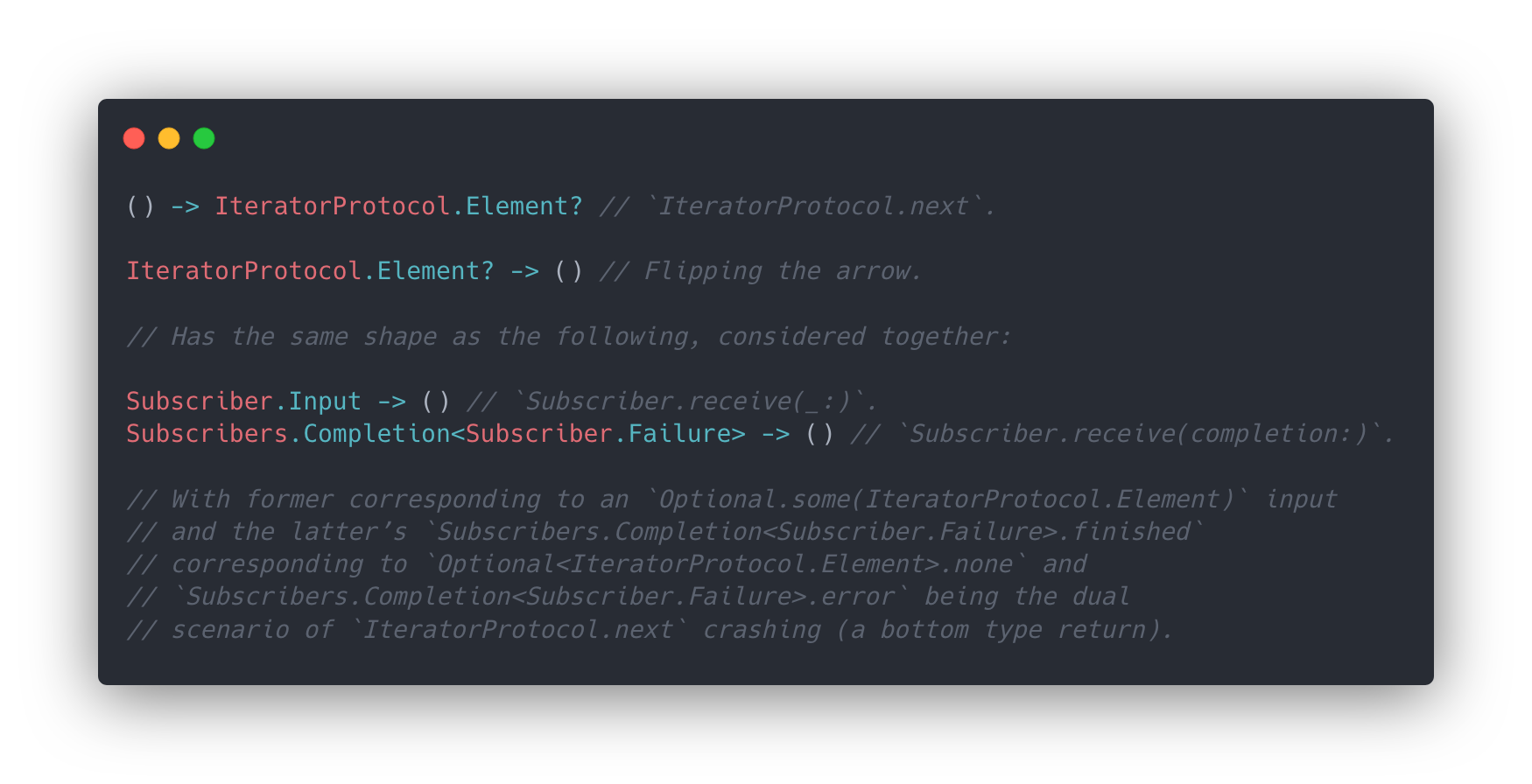

At its core, IteratorProtocol.next is a function that takes Void input and optionally returns an IteratorProtocol.Element—put another way, “pulling” the next element from the iterator.

The dual story is a function that takes an optional IteratorProtocol.Element and returns Void, with the Void return signaling either a no-op or side effects. Now for the two input cases. An Optional.some(Element) is akin to receiving the next element of a sequence and an Optional<Element>.none is a sort of terminal condition when the sequence completes.

Which, conveniently enough, mirror Subscriber.receive(_:) and Subscriber.recieve(completion:), respectively (noting that Subscriber also packs the notion of backpressure through Subscribers.Demand which isn’t reflected in the duality and error handling through Subscribers.Completion.failure(_:) that’s subtly implied by the possibility of IteratorProtocol.next crashing at runtime2). Subscriber is the dual image of IteratorProtocol in Apple’s Combine—and instead of “pulling” IteratorProtocol.Element’s, it’s a type that’s “pushed” Subscriber.Input’s

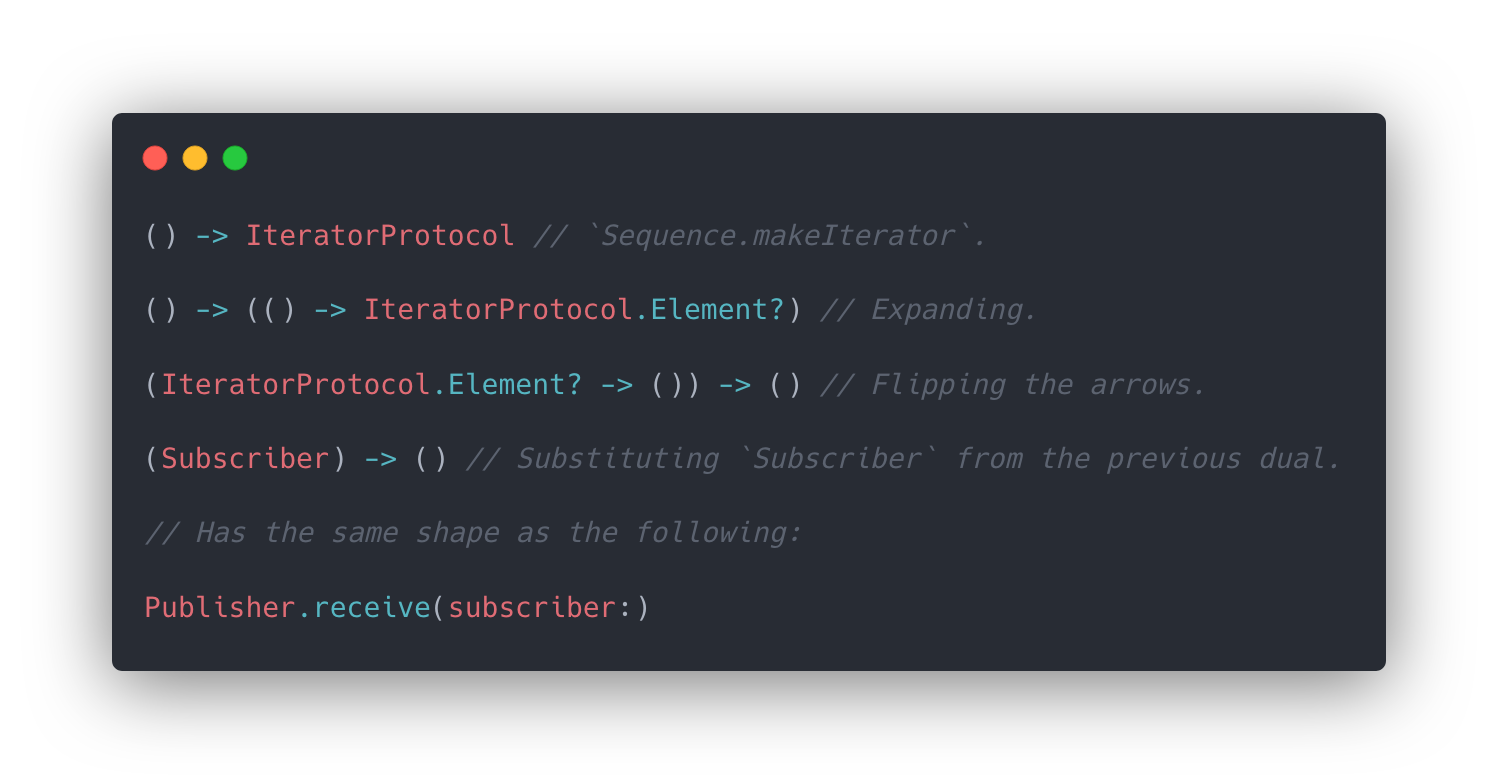

Onto Sequence. Sequence.makeIterator is a function from Void to an IteratorProtocol and, in the paragraph above, we noted that an iterator is a function from Void to Element?. So, Sequence has the following shape: () -> (() -> Element?).

“Stop! Dual time.” - MC Hammer, probably.

The dual shape is then (Element? -> ()) -> () and substituting Subscriber for Element? -> () we get a function that accepts a Subscriber and Void returns.

And that brings us to Publisher.receive(subscriber:)—the attachment point of a subscriber to a publisher.

What’s wicked about the duality between (IteratorProtocol, Sequence) and (Subscriber, Publisher) is that, well, it’s been hiding in plain sight. Apple didn’t cook up a new abstraction—they just flipped the arrows in the same way RAC did as Justin Spahr-Summers explains in his June 2014 talk on the future of the library, Brian Beckman and Erik Meijer in a March 2014 Expert to Expert video, and, most recently, as Casey Liss walked through in his post: “Building up to Combine.”

Reactive programming isn’t intrinsically harder (or newer) than imperative—it’s the dual. What requires patience is building an intuition around it in undoing our industry and academic institutions’ bias towards the imperative side of the coin.

I hope this undoing brings us to a period captured by the title of Rob Rix’s 2013 CocoaConf Columbus presentation, Postmodern Programming.

Postmodern Programming

Rix’s talk is worth multiple reads with multiple [beverage of choice]s and its core is this: declarative programming—and by extension, reactive handling of data flow—allows us to tell our programs “what” to do, instead of meticulously instructing them “how” to execute. We can then focus on the relationships between components and lean on runtimes and frameworks to determine the mechanics of how those relationships are honored.

This isn’t to say postmodern programming will be entirely declarative. There are times when imperativeness makes code more performant or incurs a smaller memory footprint, usually when the backing engine isn’t entirely sure how to optimize for a use case.

And that’s okay. If premodern programming leaned imperatively, then maybe postmodern programming is remembering the reactive dual and knowing when to lean in the other direction.

After all, Combine is just flipping the arrows.

Footnotes and related reading

⇒ In an early draft, I included a subheading on key paths (and more generally, lenses) and prisms in the “Hiding in Plain Sight” section. I’ve tucked it below to keep the post concise, yet provide another example for the curious.

Key Paths and ??? (Lenses and Prisms)

SE-0161 brought key paths to Swift and with their addition, we can traverse into deeply nested types through a series of properties and subscripts. After a couple of enhancement proposals, key paths buy us a sizable chunk of the benefits we’re afforded by a construct more generally known as lenses.

camera pans to Swift’s enumeration type upset in the corner

Sadly, there’s no first-class affordance for the dual story of traversing into branches of a nested enumeration via associated values, transforming some target value, and gluing the branch back into the enumeration. We have to write these dual structures—prisms—by hand.

Lens, prisms, and, more broadly, “optics” (not in the physics sense) is a world in and of itself. Here’s a couple of resources:

- Brandon Williams’ talk on lenses and coverage of prisms in his presentation on “Composable Reducers and Effect Systems.”

- Pickering, Gibbons, and Wu’s Profunctor Optics paper.

-

The potential for a runtime crash is a

Neverreturn value in disguise. So,Nevercan be seen as a subtype of any other type in that, if an expression doesn’t return by crashing, then it doesn’t matter what the original return type was—making this universal bottom type property explicit was an alternative considered in SE-0102. ↩