Slowing down the web

01 Jul 2018iOS 12’s “Screen Time“ might be the biggest, recent step forward in humane product design.

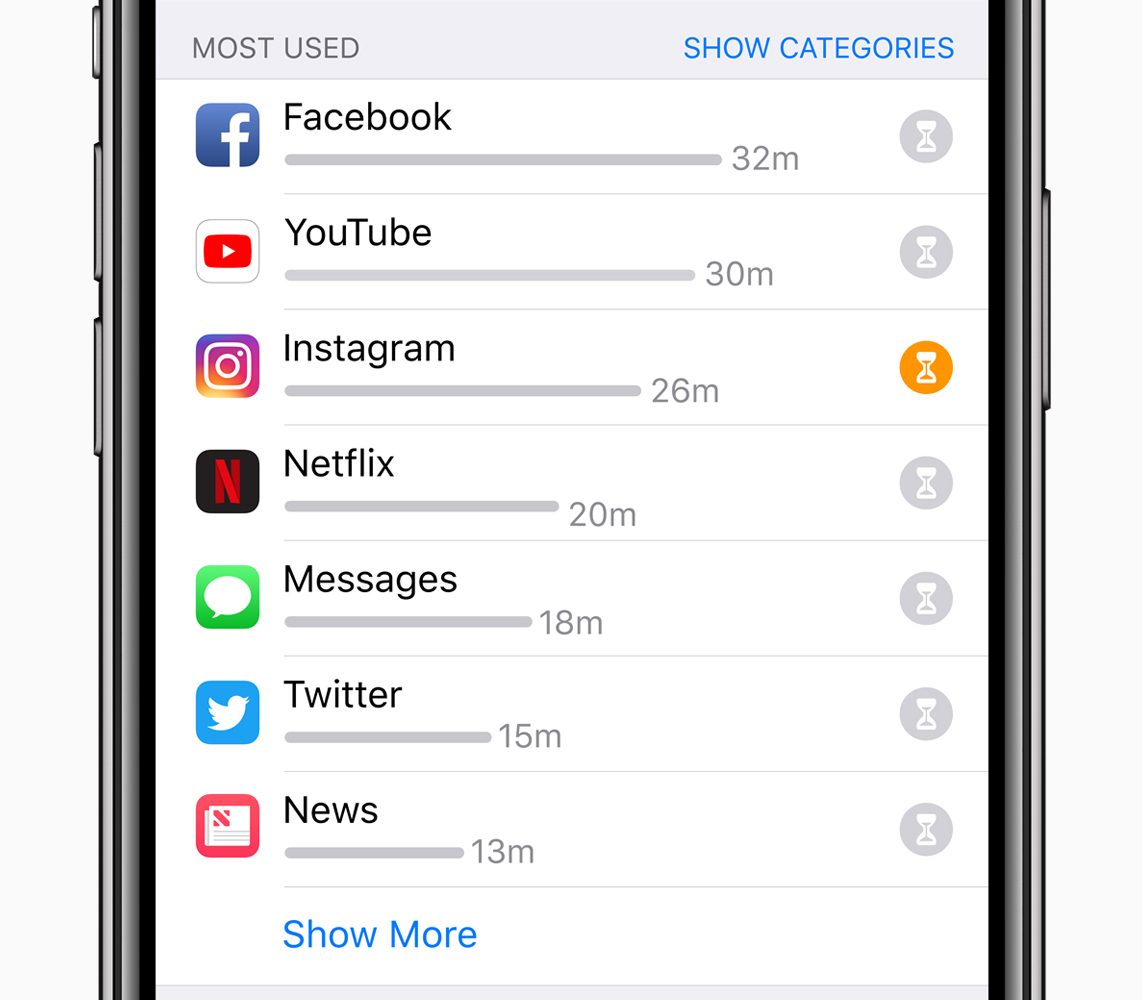

It packs usage reports, device pickup counts, enhanced Do Not Disturb controls, and granular notification settings. However, as I read the press release, I couldn’t shake the feeling that the feature Band-Aids over the networks called out—namely, Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter.

Fixing our collective relationship with these networks won’t happen overnight and I’m not advocating for their absence. Still, they could benefit from replicating aspects of the “Slow Web“—blogs, journaling, and RSS. Particularly, decoupling reading and writing, preventing engagement, and allowing users to siphon content into smaller “ponds.”

Decoupling Writing and Reading

Most networks implicitly couple the act of reading and writing. Not only are we expected to read Twitter, Instagram, or Facebook’s feeds, they’re designed for us to write back to them in the form of tweets and posts.

What if we broke this assumption? Journaling does this for me. The habit is almost purely write-only. Of the 1,943 entries (five years of memories) in my journal, I’ve only read a couple hundred—nostalgically resembling the letters high school teachers made us write to our future, university selves.

It’s healthy to gut check whether or not to read and write to networks. The conjunction might not always make sense. Personally, I use Swarm and GitHub as write-only feeds. I’ll checkin and commit, respectively, but rarely browse their feeds. There may be an opportunity for a service to use this decoupling to its advantage, as I noted in “Nostalgia and Upper Bounds.“

[I]magine if services like Twitter allowed tweets to be posted at any time, and only surfaced the feed during specific, limited hours of the day. That could do wonders in eradicating continuous partial attention [while capturing the joy of shared presence that permeates Twitter during live events].

Eliminating “Engagement”

Another trait of the Slow Web is preventing typical notions of “engagement“—likes, retweets, favorites, shares…the Lucky Charms of the Internet. RSS may be dead for all mainstream purposes (aside from quietly powering the podcast industry), but I’m a holdout. What’s special about RSS is its postal system-like nature. Feed entries arrive at a digestible pace and the protocol eliminates engagement entirely. Posts simply float out into the ether. Following my friends on both Twitter and RSS has been fascinating because of this. More specifically, when feed items aren’t cross-posted to normal social channels, it’s a small glimpse into their digital inner life.

I recently adopted the engagement-free approach for Distillations by stripping out Google Analytics. What keeps me going are those of you who have edited, provided feedback, and reached out when a post resonated. It doesn’t go unnoticed. I’ve actually kept a log of every person who has helped me over the years, no matter how small the interaction.

The Fast Web onsets engagement fatigue. Generations that have grown up mainlining the Internet are realizing this and asking themselves “What would network X look like without vanity metrics?“ Substituting Instagram for X, VSCO might be the answer. Though, the absence of one-bit reactions means higher-energy interactions. A “like” can become a sentence—“I love this photo.”—which, in the oceans of feeds we swim through, would be tiring. Siphoning from these oceans into smaller ponds helps.

Siphoning Oceans

The funny thing about Dunbar’s Number is its practically universal acceptance in physical reality, yet it’s thrown out the window in social networks1. “If the human brain is only able to remember and manage [150] relationships at a time, no wonder our systems are fried and shorting out.” I wholeheartedly believe there is a Dunbar’s Number for each of the services we use, based on its atomic unit for content. The tricky part is finding that number. For my usage of Twitter and Instagram, the limits hover at 300 and 150 accounts, respectively.

Where do the metaphorical siphon and ponds come into play? They embed themselves in tools like Instapaper and Pocket—allowing content to be siphoned into smaller ponds that we can swim through, when we’re ready. ‘Ready’ is key here. Just because a network is real-time, doesn’t mean our consumption of it has to be. This speaks a bit to my qualms around features like “Stories” in Snapchat and Instagram. It sounds obvious, but by forcing folks to become daily active users, companies are boosting short-term metrics at the cost of burning out users in the long run.

The Slow Web doesn’t prescribe lap lengths. Stumble across four blog posts you want to read while scrolling through Twitter? No sweat, save them to Instapaper and read (or don’t) when you can, without the worry of ephemerality or higher frequency feeds sending the posts into the void.

Our relationship with technology is usually metered by “time spent.“ 30 minutes per day on Instagram, 20 on Twitter, 12 on Facebook. After walking through the Slow Web, I’m starting to think measuring wall time misses the point. How a service punctuates your day is more important. Those 30 minutes may seem innocuous. But, if it translates to 60 device pickups (~3 per hour), that’s the attention-deficit equivalent of using commas, after, every, single, word, in, a, day-long, sentence. The Slow Web focuses on the punctuation. We’re free to choose non-prescribed cadences and whether to read or write to feeds, not defaulting to both. Fewer mechanisms for “engagement“ enable us to interact more honestly through words, instead of their one-bit facades. Come to think of it, the frontrunners (walkers?) of the Slow web—blogs, RSS, journaling, et al—have been around since the early days. Maybe it’s time to turn around, rejoin them, and slow down the Web.

Special thanks to Jason for feedback on early drafts of this entry.