Time under tension

12 Feb 2018Strength training is a nonnegotiable part of my routine. It has been an anchor in uneasy times, helped me look in the mirror with a palpable sense of peace, and continues to teach lessons that have cognitive analogs. I want to hone in on a particular lesson that my trainer has relayed over the past couple of years: “Time Under Tension.“

Time Under Tension (TUT) originates from a style of lifting called hypertrophy training. Unlike traditional olympic variants, which focus primarily on setting personal bests, hypertrophy is about how long a muscle is under strain. This duration of stress—up to a limit—induces physical growth. In a similar vein, endurance athletes practice heart rate zone training to get comfortable being uncomfortable. I wholeheartedly believe there is a cognitive parallel here. Some of my hardest days have involved staring at a problem for hours, clueless—a sort of mental time under tension.

I’m trying to better lean into these forms of tension. Stuck on a bug whose root cause is just out of reach? I should give it a fair shot before asking for help1. “Productively” procrastinating on what I should be working on with low hanging fruit? Likely a sign that I’m avoiding the TUT associated with my most important task. Embracing this stress fosters an internal confidence. Physically, knowing that I’ve previously endured X minutes of tension across multiple sets lets me graduate to X + 1 minutes. Mentally, it reassures me that—on a long-enough timescale—I’ll figure out whatever bug, feature, etc. I’m working on. This doesn’t imply blindly leaning into tension, knowing when to stop is just as important. Effectively distinguishing between healthy and damaging forms of tension is a skill in its own right.

A Different Lens on Top Performers

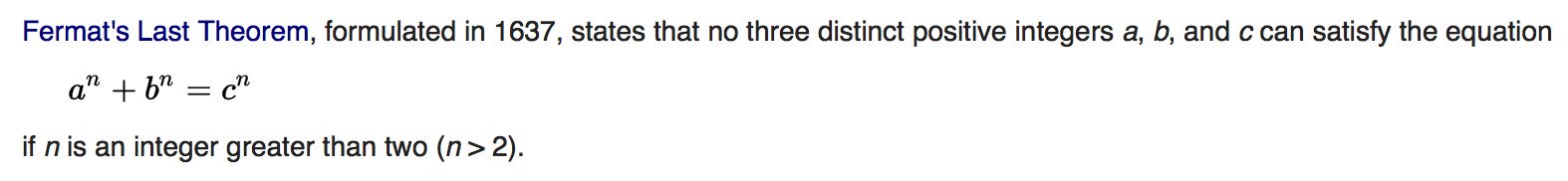

The concept of TUT reshaped how I view top performers in their respective fields. Maybe they’re not so much “gifted” as having higher physical/mental pain tolerances than the rest. The best mathematicians are masters at this. Let’s take Andrew Wiles for example. He spent seven years (!!!) proving Fermat’s Last Theorem, which can be stated in a mere three lines:

Imagine “being stuck” for the better part of a century. In the trenches of Fermat’s conjecture, Wiles built the machinery (quite literally, the proof is 129 pages long) necessary to confirm an intuition from 1637. Wiles described coming to terms with this state in a conversation with Ben Orlin.

“When it comes to math, Wiles said, people tend to believe ‘that there is something you’re born with, and either you have it or you don’t. But that’s not really the experience of mathematicians. We all find it difficult. It’s not that we’re any different from someone who struggles with maths problems in third grade…. We’re just prepared to handle that struggle on a much larger scale. We’ve built up resistance to those setbacks.’”

…Listening to Wiles, you feel this. Beneath his gentle poise, you can sense the ten-year-old boy, pouring hours into Fermat’s Last Theorem, undeterred by the centuries of failure that have come before, unafraid of the decades of work ahead.

If you hold one mental image of Wiles, he wants it to be this: not the triumphant scholar with the medal around his neck, but the child learning to glory in the state of being stuck.”

The tension that comes with challenging tasks is often avoided. But, that’s where physical and mental growth lies. By leaning into the time spent under tension, we raise our baseline pain tolerance. Greg LeMond captured this in his hallmark quote on cycling: “It doesn’t get any easier, you just get faster.”

Special thanks to Sravanti and Ravi for feedback on early drafts of this post.

Footnotes:

-

There is no hard rule here on how much time constitutes a “fair shot.“ It’ll depend on the situation. However, 15 minutes feels like a solid minimum. ↩