Seek perspectives, not mentors

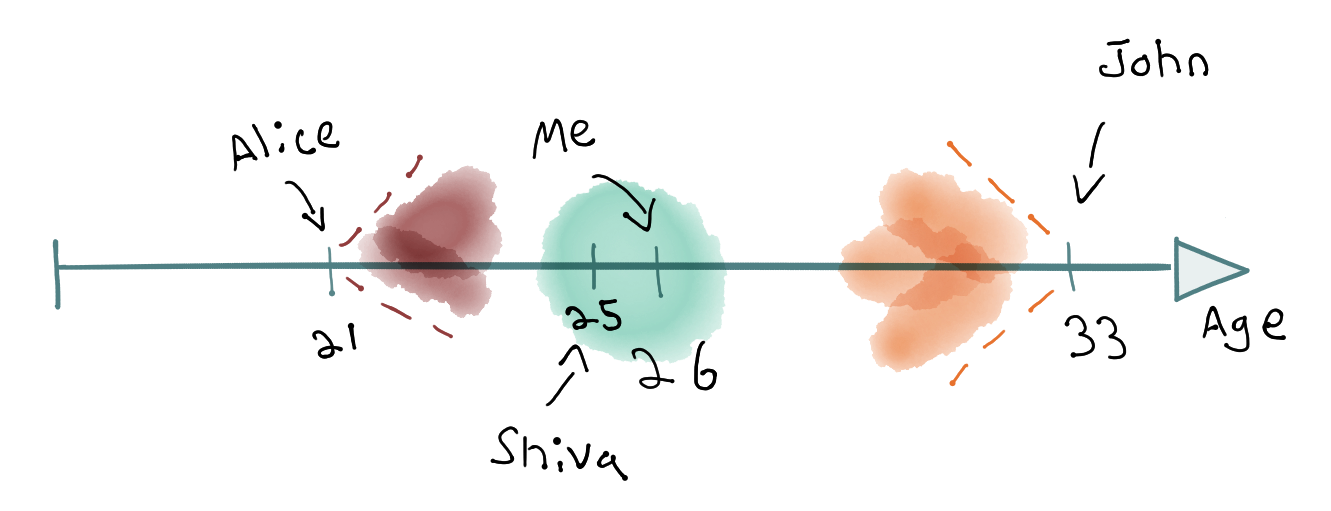

01 May 2018At the moment, I have three “mentors,” all of varying ages. Alice at 21, Shiva is 25, and John coming in at 33. Before diving in, let’s clear the air around the quotes surrounding “mentors.” I wholeheartedly believe mentorship is bidirectional and the set of folks you give this label to can, and should, change over time. This flies against the traditional notion of mentorship—making me question if it’s the right thing to seek in first place. The usual narrative claims we should find a mentor (singular) early in our careers and stay under their wing, indefinitely. In more static domains such as woodworking, that one-to-one, apprentice-like setup might be enough. However, in fields where knowledge has an incredibly short half-life—think medicine or engineering—time fogs the lens through which any one mentor can assess the context of your situation.

Perspectives are more effective and age is just one dimension to strive for variability. If we’re all in some n-dimensional space, where n is the number of axes that make us unique, then getting the most perspective on a decision will likely involve consulting folks outside your n-dimensional neighborhood.

Of course, there are two caveats here. First, constructing a peer set that covers every dimension is practically impossible. The intent is to get a large-enough span and then stand at the intersection of divergent influences. Second, this isn’t to disqualify traditional, long-term mentors—but rather to be honest in checking whether or not their experiences are relevant to your immediate situation. There are a couple of aspects to consider: knowledge half-life and longitudinal bias—we’ll dig into both and cover some ways to seek perspectives in practice.

Knowledge Half-Life

Half-life is “the time required for any specified property (e.g., the concentration of a substance in the body) to decrease by half.” Applied to knowledge, we can guess how long the things we learn today will remain relevant. The encompassing domain is important. For instance, in mathematics, half-lives are durable over longer timescales, since each finding is a deduction from previous work and axioms1. On the other hand, scientific fields like civil engineering and astrophysics move quickly, lowering half-lives. How does this tie back to mentorship? When seeking advice on a challenge you’re facing, it might be helpful to tease apart how much of the difficulty lies in knowledge with shorter half-lives versus relative invariants like emotional intelligence, architecture, and design patterns. Doing so could determine if an existing mentor or a new set of perspectives would shine more light.

Longitudinal Bias

I’ve started questioning whether or not knowing someone, longitudinally, over the arc of their career means you’re better equipped to provide advice when needed. I used to think so—and I’m starting to change my mind. A way to describe the underlying problem is “longitudinal bias”: being familiar with someone’s past subconsciously molds how you see them in your mind’s eye and sets expectations on future behavior. The problem comes when their situation requires them to break out of this mold—showing the advantage of perspectives. By consulting outside perspectives on relevant situations, we can solicit guidance that isn’t biased by our past.

In Practice

Assembling a set of perspectives while considering knowledge half-life and avoiding longitudinal bias involves putting yourself in the right “rooms“—both physically and digitally. I’m going to focus on the latter, as it’s often overlooked in mentorship discussions.

Extending a section from a previous entry, “Emotional Ranges,“ Twitter is an incredible tool for not only cultivating empathy, but also constructing a diverse peer set.

While Twitter receives a lot of rightly-deserved flak for no longer harboring a safe space for those in the minority of the aforementioned dimensions, it has the power to enable users to be deliberate about the metaphorical “rooms“ they place themselves in, for better or for worse. On the worse end, the “room“ is filled to the brim with similar walks of life, reinforcing confirmation bias. On the better end, it’s a wonderful educational tool in cultivating empathy.

Following folks from walks of life unlike your own lets you span a larger subset of the n-dimensional space we discussed earlier. An added benefit of placing your consciousness at the confluence of diverse streams of thought is that it makes independent thinking an act of discipline, rather than leaving it up to willpower.

I don’t mean to imply I’m perfect at this—my following graph is a continual work in progress. Yet, there are a couple of approaches that have helped.

First is a Twitter gender breakdown tool, Proporti.onl. The code is a bit dated, “[inaccurate,] and undercounts nonbinary folk, but it’s better than making no effort at all.” Proporti.onl has given me a frame of reference—albeit an approximation—in working towards increasing the variance of my feed.

Second is a subtle habit I’ve picked up since using Twitter over the years. Let’s assume there are two contributors, A and B, behind a major project. I’ll follow the one with fewer followers (say, B). Odds are B will bring a newer, humbler perspective into my feed and, by retweeting them, it’ll chip away at existing associations between the project and A—a reminder that our usual habits around attaching a single person to an effort inadvertently “others” contributors with a smaller online footprint. Rosa McGee is not only a friend, but a prime example of someone who brings such a perspective to my timeline. She may not have the “largest following” amongst theSkimm’s team. Yet, I always pause to read her thoughts on Twitter.

This speaks a bit to my qualm around Twitter Lists and “you should follow {Q, R, S, T…}”-style tweets. Having a surface area on Twitter isn’t necessarily correlated with skill.

It’s healthy to challenge whether or not traditional, apprentice-style mentorship still works. The term “mentor“ can lead to uncomfortable and untrue pedestals—making me lean towards perspectives. By reaching out to people from walks of life unlike your own, you can illuminate a larger neighborhood of the n-dimensional space your career is navigating through. Digitally, we’re currently afforded this ability through Twitter. Instead of having a handful of lenses on the world with in-person mentorship, I have 311. You’d be surprised how willing people are to lend a hand. In fact, I’ve made some of my best friends by seeking perspectives, not mentors.

Special thanks to Alice, Shiva, Rosa, and John for feedback on early drafts of this entry.

Related reading and footnotes:

⇒ “Have Some Coffee”

⇒ “On Mentoring”

⇒ “72% Of The People I Follow On Twitter Are Men”

⇒ “Lists of Women Don’t Change Anything”

⇒ “Why Twitter Is Dope And How To Use It”

-

In editing, John pointed out a nuance that knowledge in mathematics is rarely invalidated, but often superseded. The distinction is important. Unlike other fields in which prior knowledge is frequently proven incorrect, the structure of mathematics forces correctness through proofs. Yet, the techniques and approaches used can often be made obsolete in the future (e.g. integrals instead of Riemann sums). ↩