Ladder construction

28 May 2018Were the four years I spent at university worth it? With 2018 marking a school-length after graduation, the question has been top of mind. My unmeditated answer is yes; UVA was incredibly formative. Still, I’ve just recently put a finger on why. Universities construct “ladders.” Just because coursework is increasingly becoming available online doesn’t imply we can make effective traversals of that content. Schooling provides said content and creates a ladder—allowing us to focus on climbing through the material, instead of trying to simultaneously climb a ladder we’re building.

School is one of the many forms ladders can take. My peers who made the least turbulent transitions after graduation were those who could continue to build ladders outside structured educational environments—knowing when to delegate construction externally versus internal construction.

Ladder Spectrum

Ladders serve two functions: a guided traversal through a domain—think sport or subject matter—and a feedback loop in countering our tendency towards mean reversion. The spacing between the rungs on the ladder represent the resolution of the traversal. Are you being instructed from concept to concept or sporadically checking in for accountability? A feedback loop should occur at each rung, allowing for course correction.

Who (or what) builds these ladders for us? Under this lens, a spectrum of solutions comes into sight: groups, friends, and coaches/managers.

Groups

On one end, we have groups. They can take shape as running clubs, traditional classroom settings, or meditation groups. The last example has been particularly impactful. I’ve used Headspace for the better part of the past five years. Still, I’d regularly hit “plateaus.” The periods are hard to describe—but, I felt it. Sits started resembling a chore more than a 20-minute enclave in my day. I needed a ladder and a now-defunct group in NYC, Balanced, built one for me in climbing out of these plateaus.

Week over week, we’d meet in Casey and Leo’s SoHo loft, sit for 20 minutes, sift through a passage on topics like transitions, burnout, “being enough,” and then wrap up with a group discussion. Even though the volume of my practice was roughly the same between Headspace and Balanced, translating it from a single-player journey to a ladder we all climbed, together, made the difference.

Two nuances crop up in group settings: whether or not a teacher or peer set provides the feedback loop and the fact that larger groups tend to construct ladders that don’t fit each individual well.

The first nuance reminds me of a thought from Nikhil.

Because your peers didn't have any say in your grade, you just needed to learn the rules the teacher had and play by them properly

— Nikhil Krishnan (@nikillinit) October 1, 2017

In ladders where evaluation comes from a single person, e.g. a teacher, climbing faster might mean learning their rules and playing by them properly. This is probably innocuous in most cases—but it becomes a problem when the teacher’s rules diverge from the course corrections you actually need to make. Evaluation by a peer set (or multiple perspectives) could be more effective. An issue with peer evaluation is that the set is usually small for in-person contexts—pointing to a hybrid approach between IRL and Internet peers as a remedy. Still, that approach causes the second nuance, larger groups tend towards building inaccurate ladders. There will be times where you want to climb faster or slower than the ladder—moving along the spectrum helps with this.

Friends

Friends land between groups and coaches/managers as a ladder constructors. My most-cherished friendships have had the trait of inciting sustained, personal growth—Shiva being the one I’m most thankful for.

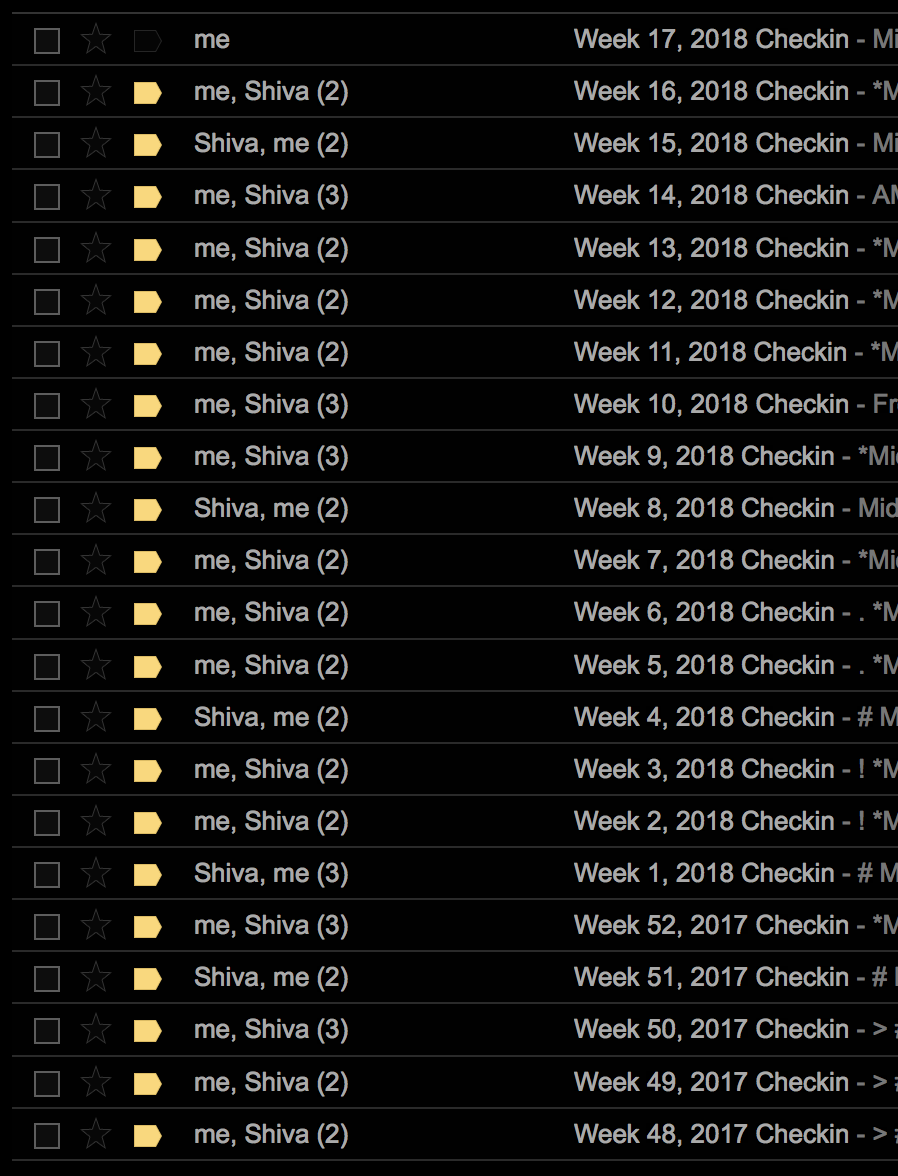

Over the past year, we’ve added a rung between our monthly checkins: a weekly email recapping the progress we’ve made towards our respective goals. The format is dead simple.

# Midterm Goals:

# Goal(s) for the week:

# What got done?

# Honorable Mentions:

# Goals for the upcoming week:

38 checkins later, I can honestly say this accountability ladder has single-handedly driven Distillations (this collection) closer to my longer-term goals.

The weekly cadence is key—long enough to make tangible progress, yet short enough to limit time lost from procrastinating. With only monthly calls, I would punt work to just before the checkin, losing a possible month of headway. Tightening the rungs of our ladder from four weeks to one let us course correct more frequently. There’s a downside though; by increasing the cadence, we often lost sight of the forest. So, we’ve kept our monthly FaceTime calls as an opportunity to zoom out and work through any concerns that shook out in the weeks beforehand.

Coaches and Managers

Coaches and managers land on the other end of the spectrum. I used to wonder why world-class athletes and CEOs were commonly cited as roles that necessitated coaching, leaving a gap for the rest of us. However, if you squint hard enough, coaches and managers are practically the same thing. Effective managers not only serve as umbrellas for their team, but also provide reports with regular feedback loops and guidance in climbing a company’s (sometimes-existent) career ladder.

An added benefit of this one-to-one dynamic is specificity. Ladders are built to your trajectory, context, and preferences, instead of being muddied by group constraints. “Luck” is teased apart by appropriately spaced rungs—better correlating efforts and outcomes.

Intuition

There’s a leap to be made between recognizing the spectrum and knowing how to move along it. Deploying this intuition can prevent progress from reverting to the mean and be especially helpful in trying times. I learned this three years ago during an extended struggle with mental health.

To paint context, a major part of my life is strength training. I started back in 2009—researching workouts, form, and techniques. The activity quickly became “an anchor in uneasy times, helped me look in the mirror with a palpable sense of peace, and continues to [teach me lessons].” Everything was incrementally smooth sailing until February of 2016, when I had a close call while deadlifting. I nearly passed out. The ensuing check-ups to rule out any potential injuries induced a constant, lingering worry in my mind. Two months of medical stress began affecting other areas of my life. Experiences I never thought twice about—exercise, flights, public speaking—became coated with anxiety.

Prior, I kept my mental and physical health in check through self-paced meditation and workouts—building my own ladders. Hitting rock bottom that winter forced me to admit I couldn’t do it all myself. Instead of flying solo, I decided to delegate ladder construction externally through therapy and hiring a coach. The two provided shorter feedback loops, gradually elevating my baselines. All I had to do was show up and put in the physical and emotional labor. Over the following six months, I weathered the collectively familiar, yet internal wars that are mental health struggles. If I hadn’t admitted I needed help and let others build ladders, that rut may have lasted longer.

It’s easier to trust externally constructed ladders. The hardest part of building while climbing is critiquing your own strategy, because you’re doing three things simultaneously: building the ladder, working up it, and revising the entire process. But, this doesn’t mean we should shy away from internal construction—instead, forming an intuition of the ladder spectrum in different areas of our lives is key.

I’m shaping my intuition when it comes to this site. While I’ve kept pace with writing, I feel like I’m on a treadmill—churning out post after post, locally improving (hopefully) with each one, without a larger “mile marker” in sight. It might be time to let someone (or something) else build a ladder here—until then, I’ll keep climbing.

Special thanks to Gwen and Shiva for feedback on early drafts of this entry.